The Danial Latifi Case and the Indian Supreme Court’s Balancing Act Islamic law is before the Supreme Court of India again, with the question of whether triple-ṭalāq is a valid way of dissolving a marriage: by a man simply pronouncing that his wife is divorced by saying that word three times. To understand where the Court might be going requires a bit of background. Following the 1985 Shah Bano case in India, the Indian Supreme Court was faced with protests from the Indian Muslim community over its perceived interference in Islamic personal law. This response revealed the political complexity of executing the Supreme Court’s dedication to defending the constitutional rights of all its citizens. India editor Akhila Kolisetty uses the passage of the 1986 Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act in 1986 and the Danial Latifi v. Union of India (2001) that followed to explicate the Indian Supreme Court’s unenviable position of balancing gender and religious equity. The Muslim Women Act of 1986 limited maintenance payments to the iddat period (the three-month waiting period for divorce in Islamic law), leading to negative responses from women’s rights organizations. Danial Latifi, Shah Bano’s lawyer, challenged the constitutionality of the Act, calling it discrimination against Muslim women on the basis of their religion. Under the Act, women were excluded from the protections of the Indian Constitution’s Articles 14, 15, and 21. The Court resolved this constitutionality quagmire by finding that a Muslim husband must pay the “reasonable and fair amount needed to maintain his ex-wife for the rest of her life…in total during the iddat period.” This type of understated but sufficient solution “exemplifies a pattern within the Supreme Court’s approach to Muslim personal law: claims that “promote Muslim women’s gender equity while also limiting [the Court’s] intervention into Islamic personal law to avoid potential backlash.” Read more. Image credit: Wikipedia

The Danial Latifi Case and the Indian Supreme Court’s Balancing Act Islamic law is before the Supreme Court of India again, with the question of whether triple-ṭalāq is a valid way of dissolving a marriage: by a man simply pronouncing that his wife is divorced by saying that word three times. To understand where the Court might be going requires a bit of background. Following the 1985 Shah Bano case in India, the Indian Supreme Court was faced with protests from the Indian Muslim community over its perceived interference in Islamic personal law. This response revealed the political complexity of executing the Supreme Court’s dedication to defending the constitutional rights of all its citizens. India editor Akhila Kolisetty uses the passage of the 1986 Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act in 1986 and the Danial Latifi v. Union of India (2001) that followed to explicate the Indian Supreme Court’s unenviable position of balancing gender and religious equity. The Muslim Women Act of 1986 limited maintenance payments to the iddat period (the three-month waiting period for divorce in Islamic law), leading to negative responses from women’s rights organizations. Danial Latifi, Shah Bano’s lawyer, challenged the constitutionality of the Act, calling it discrimination against Muslim women on the basis of their religion. Under the Act, women were excluded from the protections of the Indian Constitution’s Articles 14, 15, and 21. The Court resolved this constitutionality quagmire by finding that a Muslim husband must pay the “reasonable and fair amount needed to maintain his ex-wife for the rest of her life…in total during the iddat period.” This type of understated but sufficient solution “exemplifies a pattern within the Supreme Court’s approach to Muslim personal law: claims that “promote Muslim women’s gender equity while also limiting [the Court’s] intervention into Islamic personal law to avoid potential backlash.” Read more. Image credit: Wikipedia

LEGISLATION:: Muslim Women Protection Act of 1986 The Muslim Women Protection of Divorce Rights for Muslim Women Act was passed in 1986 in response to the Muslim Indian community’s outcry against the Indian Supreme Court’s decision in the Shah Bano case (1985). The Court held that a Muslim husband must pay maintenance amounts to his ex-wife for life-maintenance during the divorce waiting period. But many Muslim leaders considered this to be an intrusion onto their practice and perspectives on traditional Islamic personal law. The Act in effect overrode the Court’s decision of 1985, limiting maintenance provisions to those that would be due during the divorce-waiting period alone (traditionally three months). Read more. Image credit: India Times

LEGISLATION:: Muslim Women Protection Act of 1986 The Muslim Women Protection of Divorce Rights for Muslim Women Act was passed in 1986 in response to the Muslim Indian community’s outcry against the Indian Supreme Court’s decision in the Shah Bano case (1985). The Court held that a Muslim husband must pay maintenance amounts to his ex-wife for life-maintenance during the divorce waiting period. But many Muslim leaders considered this to be an intrusion onto their practice and perspectives on traditional Islamic personal law. The Act in effect overrode the Court’s decision of 1985, limiting maintenance provisions to those that would be due during the divorce-waiting period alone (traditionally three months). Read more. Image credit: India Times

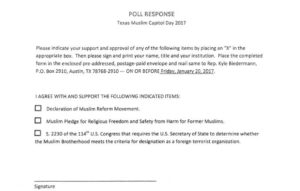

TRENDING: When Is a Texas “Poll” about Sharīʿa Not Really a Poll and Not Really about Sharīʿa? A Texas state legislator, Representative Kyle Biedermann, recently sent out what he called a poll to mosques across the state. It was a seven-page series of documents that selectively drew on false notions of Islamic law (i.e. sharīʿa) that are uninformed by fact, history, or sociological practice. Sharīʿa , in fact, is the Arabic word for an ideal of justice, and often is used to refer to fiqh — manmade constructions of that ideal. To refer to either is to refer to a broad and diverse legal system that is informed by different cultural contexts, scholarly interpretations, and community discussions over time and space. These facts’ absence from the poll underscore the need for more informed discussion about Islamic law, or sharīʿa, especially as it becomes more and more a matter of local and national debate in our legislatures and courts. Image Credit: SHARIAsource

TRENDING: When Is a Texas “Poll” about Sharīʿa Not Really a Poll and Not Really about Sharīʿa? A Texas state legislator, Representative Kyle Biedermann, recently sent out what he called a poll to mosques across the state. It was a seven-page series of documents that selectively drew on false notions of Islamic law (i.e. sharīʿa) that are uninformed by fact, history, or sociological practice. Sharīʿa , in fact, is the Arabic word for an ideal of justice, and often is used to refer to fiqh — manmade constructions of that ideal. To refer to either is to refer to a broad and diverse legal system that is informed by different cultural contexts, scholarly interpretations, and community discussions over time and space. These facts’ absence from the poll underscore the need for more informed discussion about Islamic law, or sharīʿa, especially as it becomes more and more a matter of local and national debate in our legislatures and courts. Image Credit: SHARIAsource

See the full newsletter.